Albrecht Dürer’s material world:

Albrecht Dürer’s material world:

How to make an exhibition

Albrecht Dürer’s material world:

Albrecht Dürer’s material world:

How to make an exhibition

Albrecht Dürer’s material world: How to make an exhibition

Albrecht Dürer was one of the most important figures of the Northern Renaissance, and made significant impact as a printmaker. ‘Albrecht Dürer’s material world’, which opened at the Whitworth on 30 June 2023, is the first major exhibition of the Whitworth’s outstanding Dürer collection in over half a century. The exhibition displays Dürer’s intricate woodcut prints, engravings and etchings in context, presenting Dürer’s fascination with the changing Renaissance material world by juxtaposing his artworks with objects that were sources of inspiration for the artist. To celebrate the opening of the Whitworth’s exhibition, I have written a short blog exploring some of the processes behind making the exhibition, specifically the preparation of birds, prints, and books for display.

Albrecht Dürer, Nemesis (c. 1501), engraving, The Whitworth, P3019. © The Whitworth, The University of Manchester.

The artefacts displayed come from a number of collections. I started my investigation by examining Nemesis (c. 1501) – the print chosen for the catalogue cover – and was immediately struck by the intricacy of the goddess’s feathered wings. Many historians believe that these wings were based on Dürer’s study painting The Wing of a Roller (c. 1500).

Albrecht Dürer, The Wing of a Roller (c. 1500), watercolour and opaque colours, raised with opaque white, on very fine, smoothed and polished parchment, ALBERTINA, Vienna, 4840. © The Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Indian and European Roller Bird Specimens at the Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester. Photo: Riana Shah.

I was amazed to learn that the Whitworth planned to exhibit study skins from an Indian roller bird and a European roller bird from Manchester Museum’s collection. In a meeting with Imogen Holmes-Roe (Curator-Historic Fine Art at the Whitworth and co-curator of the exhibition) and Jenny Discombe (Conservator at Manchester Museum), I learnt that the exhibition would also display an orange-winged Amazon Parrot specimen – the tropical bird seen in the top left of Dürer’s Adam and Eve (1504) engraving.

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve (1504), engraving, Ashmolean Museum, WA.RS.STD.010, P3019. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

The Collection Care team were still in the early processes of preparing the birds for the exhibition, so the discussion mostly focused on confirming the angle and position of the birds’ placement. They planned to display the orange-winged Amazon Parrot beside Dürer’s Adam and Eve, mounted similarly to how it perches on a branch in the artist’s print. This was agreed quite easily and measurements were taken.

Measuring the Amazon Parrot at Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester. Photo: Riana Shah.

The conversation then turned to the display of the roller birds and how best to present them while ensuring their conservation needs were met. The birds will be in a display case, and for conservation purposes the roller birds must be kept on their back and cannot be angled too harshly; however, for viewing purposes, the more elevated the angle the better it would be. It was agreed to display the birds at 30 degrees, using a fabric-covered slope to prevent them sliding down and pins as extra support to hold them in place.

My next meeting was with Daniel Hogger, the Whitworth’s Works on Paper Conservator. Dan ran me through the whole process of preparing prints for display, which starts with the curator choosing works from their collection and using the gallery collections database (which includes important conservation history, such as to where, and for how long, an item has previously been loaned for display). The next step is for Dan to assess the artworks’ condition and write up a treatment proposal for each work; and finally, the conservators prepare the works so that they are ready for display.

First, Dan explained the importance of pH levels in conservation. He taught me that acid degradation - alongside poor handling and storage techniques - is a large contributor to an artwork’s damage. Most artworks in the Whitworth’s collections are made of organic material, which means that factors such as excessive sunlight promote acidification and speed up the degradation of works – hence, whenever we experience gallery spaces with controlled lighting or a slightly chilly feel, we should understand the conservation reasons.

Before undertaking any aqueous cleaning of a print, Dan explained the importance of spot-testing each area of the print to ensure there are no fugitive areas (sections which may have been previously missing and then filled in by draftsmen with bleed-able black ink). Next the conservators begin by surface cleaning both the front and the back of the print to remove any surface soiling; if there is any soiling left on the print, it will spread and leave tide marks.

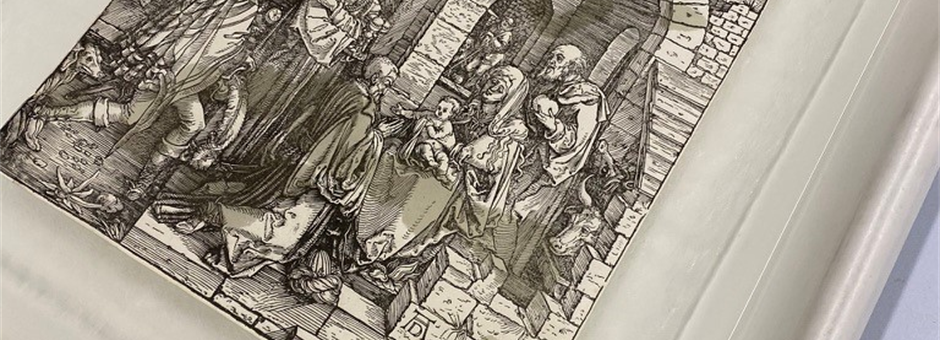

With those crucial essentials out of the way, we moved on to what I found the most surprising – seemingly ‘soaking’ prints. I was shocked by how much water is used in the aqueous cleaning processes, as we have always been told to keep liquid away from an artwork! First, the print is humidified to relax the paper support and to help release any adhesives-residue or mounting tapes that are attached to the back of the print. Then the print is supported on a piece of Holytex and lowered onto the surface of a water bath. The image shows a print undergoing a ‘float wash’. This cleaning technique uses the natural movement of water to allow water to slowly soak through the print, pick up soiling and take it back down into the water. Its cycle-like movement reminded me of a convection current. Next, the print is air dried and then pressed between blotting paper and bondina to complete the drying process. The conservator can then undertake any paper repairs that may be needed and finally the print is mounted into an archival mount, prior to its framing for the exhibition.

Float wash of a print at the Whitworth, The University of Manchester. Photo: Riana Shah.

Finally, I met with Mark Furness (Senior Conservator at the John Rylands Research Institute and Library) to learn about the approach to preparing historical books for public display. Books often sit in bespoke cradles made from museum board and foam, and, like the roller bird specimens, should only be angled as high as 20–30 degrees in order to prevent damage. This is largely to do with the damaging effect of gravity on a book. When positioned at an angle, gravity will pull the pages of a book down, and with time, this will cause the pages to pull, distort and perhaps detach from the spine. The images demonstrate how foam is placed in any gap between the pages and the cradle’s supporting surface due to the cover board extending beyond the pages. Similarly to what Dan had said about the prints, books are organic materials which can experience rapid oxidation, and consequently degradation, if not stored and displayed correctly. Therefore, John Rylands constructs its book cradles from a pH-neutral, archival museum board, which is not prone to corrosion.

Assessing the placement of foam between pages and cradle at the John Rylands Research Institute and Library. Photo: Riana Shah.

Assessing the fit of book, cradle and foam at John Rylands Research Institute and Library. Photo: Riana Shah.

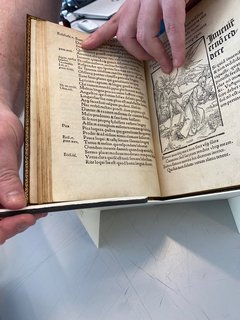

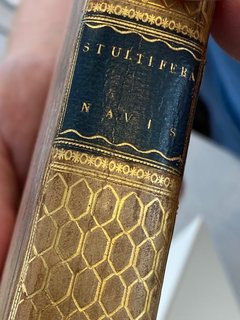

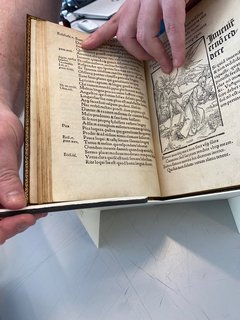

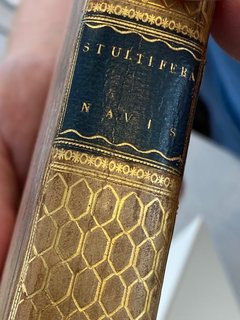

Mark addressed the difficulties of reconciling conversation needs with loan requests. For example, the co-curators of the exhibition had requested a nine-month loan of a printed copy of Sebastian Brandt’s Ship of Fools in the John Rylands’ collections to display a page showing the devil blowing on the back of a fool looking for treasure. However, to prevent over-exposure and avoid risk of conservation damage each book should be on display for no longer than six months (maximum) and have rest periods of two to three years between loans. The reason is due to the materials used for the pages and book boards (covers), as well as for inks and paints. One issue is that when books are bound in parchment, which has been stretched and dried under tension, their spines may begin to crack or distort, and not close if they are held open for too long. To manage this for the nine months of the exhibition, the John Rylands is loaning the Whitworth two copies of the book, which include the desired print, to be shown for a few months each.

Sebastian Brant, The Ship of Fools showing slight cracking on cover spine, The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester, Spencer 9793. Photo: Riana Shah.

I hope this glimpse into some of the preparation of the artefacts that inspired Dürer’s prints inspires you to go and visit ‘Albrecht Dürer’s material world’, and possibly view the exhibition in a different light – with conservation in mind.

Riana Shah

Friends of the Whitworth Student Ambassador

BA History of Art Second-Year Undergraduate, University of Manchester

July 2023

Albrecht Dürer’s material world: How to make an exhibition

Albrecht Dürer was one of the most important figures of the Northern Renaissance, and made significant impact as a printmaker. ‘Albrecht Dürer’s material world’, which opened at the Whitworth on 30 June 2023, is the first major exhibition of the Whitworth’s outstanding Dürer collection in over half a century. The exhibition displays Dürer’s intricate woodcut prints, engravings and etchings in context, presenting Dürer’s fascination with the changing Renaissance material world by juxtaposing his artworks with objects that were sources of inspiration for the artist. To celebrate the opening of the Whitworth’s exhibition, I have written a short blog exploring some of the processes behind making the exhibition, specifically the preparation of birds, prints, and books for display.

Albrecht Dürer, Nemesis (c. 1501), engraving, The Whitworth, P3019. © The Whitworth, The University of Manchester.

The artefacts displayed come from a number of collections. I started my investigation by examining Nemesis (c. 1501) – the print chosen for the catalogue cover – and was immediately struck by the intricacy of the goddess’s feathered wings. Many historians believe that these wings were based on Dürer’s study painting The Wing of a Roller (c. 1500).

Albrecht Dürer, The Wing of a Roller (c. 1500), watercolour and opaque colours, raised with opaque white, on very fine, smoothed and polished parchment, ALBERTINA, Vienna, 4840. © The Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Indian and European Roller Bird Specimens at the Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester. Photo: Riana Shah.

I was amazed to learn that the Whitworth planned to exhibit study skins from an Indian roller bird and a European roller bird from Manchester Museum’s collection. In a meeting with Imogen Holmes-Roe (Curator-Historic Fine Art at the Whitworth and co-curator of the exhibition) and Jenny Discombe (Conservator at Manchester Museum), I learnt that the exhibition would also display an orange-winged Amazon Parrot specimen – the tropical bird seen in the top left of Dürer’s Adam and Eve (1504) engraving.

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve (1504), engraving, Ashmolean Museum, WA.RS.STD.010, P3019. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

The Collection Care team were still in the early processes of preparing the birds for the exhibition, so the discussion mostly focused on confirming the angle and position of the birds’ placement. They planned to display the orange-winged Amazon Parrot beside Dürer’s Adam and Eve, mounted similarly to how it perches on a branch in the artist’s print. This was agreed quite easily and measurements were taken.

Measuring the Amazon Parrot at Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester. Photo: Riana Shah.

The conversation then turned to the display of the roller birds and how best to present them while ensuring their conservation needs were met. The birds will be in a display case, and for conservation purposes the roller birds must be kept on their back and cannot be angled too harshly; however, for viewing purposes, the more elevated the angle the better it would be. It was agreed to display the birds at 30 degrees, using a fabric-covered slope to prevent them sliding down and pins as extra support to hold them in place.

My next meeting was with Daniel Hogger, the Whitworth’s Works on Paper Conservator. Dan ran me through the whole process of preparing prints for display, which starts with the curator choosing works from their collection and using the gallery collections database (which includes important conservation history, such as to where, and for how long, an item has previously been loaned for display). The next step is for Dan to assess the artworks’ condition and write up a treatment proposal for each work; and finally, the conservators prepare the works so that they are ready for display.

First, Dan explained the importance of pH levels in conservation. He taught me that acid degradation - alongside poor handling and storage techniques - is a large contributor to an artwork’s damage. Most artworks in the Whitworth’s collections are made of organic material, which means that factors such as excessive sunlight promote acidification and speed up the degradation of works – hence, whenever we experience gallery spaces with controlled lighting or a slightly chilly feel, we should understand the conservation reasons.

Before undertaking any aqueous cleaning of a print, Dan explained the importance of spot-testing each area of the print to ensure there are no fugitive areas (sections which may have been previously missing and then filled in by draftsmen with bleed-able black ink). Next the conservators begin by surface cleaning both the front and the back of the print to remove any surface soiling; if there is any soiling left on the print, it will spread and leave tide marks.

With those crucial essentials out of the way, we moved on to what I found the most surprising – seemingly ‘soaking’ prints. I was shocked by how much water is used in the aqueous cleaning processes, as we have always been told to keep liquid away from an artwork! First, the print is humidified to relax the paper support and to help release any adhesives-residue or mounting tapes that are attached to the back of the print. Then the print is supported on a piece of Holytex and lowered onto the surface of a water bath. The image shows a print undergoing a ‘float wash’. This cleaning technique uses the natural movement of water to allow water to slowly soak through the print, pick up soiling and take it back down into the water. Its cycle-like movement reminded me of a convection current. Next, the print is air dried and then pressed between blotting paper and bondina to complete the drying process. The conservator can then undertake any paper repairs that may be needed and finally the print is mounted into an archival mount, prior to its framing for the exhibition.

Float wash of a print at the Whitworth, The University of Manchester. Photo: Riana Shah.

Finally, I met with Mark Furness (Senior Conservator at the John Rylands Research Institute and Library) to learn about the approach to preparing historical books for public display. Books often sit in bespoke cradles made from museum board and foam, and, like the roller bird specimens, should only be angled as high as 20–30 degrees in order to prevent damage. This is largely to do with the damaging effect of gravity on a book. When positioned at an angle, gravity will pull the pages of a book down, and with time, this will cause the pages to pull, distort and perhaps detach from the spine. The images demonstrate how foam is placed in any gap between the pages and the cradle’s supporting surface due to the cover board extending beyond the pages. Similarly to what Dan had said about the prints, books are organic materials which can experience rapid oxidation, and consequently degradation, if not stored and displayed correctly. Therefore, John Rylands constructs its book cradles from a pH-neutral, archival museum board, which is not prone to corrosion.

Assessing the placement of foam between pages and cradle at the John Rylands Research Institute and Library. Photo: Riana Shah.

Assessing the fit of book, cradle and foam at John Rylands Research Institute and Library. Photo: Riana Shah.

Mark addressed the difficulties of reconciling conversation needs with loan requests. For example, the co-curators of the exhibition had requested a nine-month loan of a printed copy of Sebastian Brandt’s Ship of Fools in the John Rylands’ collections to display a page showing the devil blowing on the back of a fool looking for treasure. However, to prevent over-exposure and avoid risk of conservation damage each book should be on display for no longer than six months (maximum) and have rest periods of two to three years between loans. The reason is due to the materials used for the pages and book boards (covers), as well as for inks and paints. One issue is that when books are bound in parchment, which has been stretched and dried under tension, their spines may begin to crack or distort, and not close if they are held open for too long. To manage this for the nine months of the exhibition, the John Rylands is loaning the Whitworth two copies of the book, which include the desired print, to be shown for a few months each.

Sebastian Brant, The Ship of Fools showing slight cracking on cover spine, The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester, Spencer 9793. Photo: Riana Shah.

I hope this glimpse into some of the preparation of the artefacts that inspired Dürer’s prints inspires you to go and visit ‘Albrecht Dürer’s material world’, and possibly view the exhibition in a different light – with conservation in mind.

Riana Shah

Friends of the Whitworth Student Ambassador

BA History of Art Second-Year Undergraduate, University of Manchester

July 2023

Comments & Discussion

No comments to display